Subsidized Railroads

Hill & the Great Northern

Crony Politics & Lobbying

Free Trade vs. Regulation

Conclusion

The story of the building of the transcontinental railroads makes for good reading. It has a sound plot: four railroads get charters and subsidies to build across the country. It has suspense: the Union Pacific and Central Pacific frantically race across plains and over mountains to complete the railroad. It has an all-star cast: U. S. Presidents, army generals, and political adventurers confront Indians on the warpath, politicians on the take, and thousands of Chinese and Irish workers. The story tells of the agony of defeat - Indian raids and winter storms - and the thrill of victory with the meeting of the Union and Central Pacific in Utah and the final hammering of the golden spike. Finally, there is celebrating as the story ends: Western Union telegraphs the event across the nation, and revelers sound the Liberty Bell from Independence Hall.

Over the years historians have told this story and described the drama, but they have often criticized the main actors and their exploits. The grab for federal subsidies seems to have led to greed and corruption; but - and this is the key point - most historians say there was no way to get the happy ending to the transcontinental story without federal aid. "Unless the government had been willing to build the transcontinental lines itself," John Garraty typically asserts, "some system of subsidy was essential."[1]

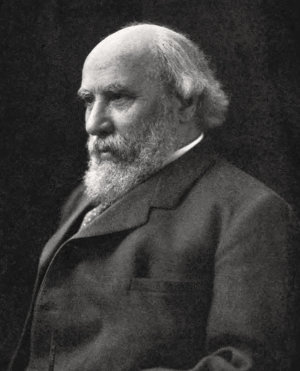

James J. Hill: Founded Great Northern RR

But there is a nagging problem in this argument. While some of this rush for subsidies was still going on, James J. Hill was building a transcontinental from St. Paul to Seattle with no federal aid whatsoever. Also, Hill's road was the best built, the least corrupt, the most popular, and the only transcontinental never to go bankrupt. It took longer to build than the others, but Hill used this time to get the shortest route on the best grade with the least curvature. In doing so, he attracted settlement and trade by cutting costs for passengers and freight. Could it be that, in the long run, the subsidies may have corrupted railroad development and hindered economic growth? The transcontinental story is worth a more careful look. It may have a different ending if we move Hill from a cameo role to that of a leading actor.

Subsidized Railroads and Political Entrepreneurs

The dream of a transcontinental had excited promoters and patriots ever since the Mexican War and the acquisition of California. Congress spent $150,000 during the 1850s surveying three possible routes from the Mississippi River to the west coast. In 1862, with the Southern Democrats out of the union, Congress hastily passed the Pacific Railroad Act. This act led to the creating of the Union Pacific, which would lay rails west from Omaha, and the Central Pacific, which would start in Sacramento and build east. Since congressmen wanted the road built quickly, they did two key things. First, they gave each line twenty alternate sections of land for each mile of track completed. Second, they gave loans: $16,000 for each mile of track of flat prairie land, $32,000 per mile for hilly terrain, and $48,000 per mile in the mountains.[2]

The UP and CP, then, would compete for government largess. The line that built the most miles would get the most cash and land. The land, of course, would be sold; and this way the railroad would be financed. In this arrangement, the incentive was for speed, not efficiency. The two lines spent little time choosing routes; they just laid track and cashed in.

Thomas Durant - United Pacific VP

The subsidies shaped the UP builders' strategy in the following ways. They moved west from Omaha in 1865 along the Platte River. Since they were being paid by the mile, they sometimes built winding, circuitous roads to collect for more mileage. For construction they used cheap and light wrought iron rails, soon to be outmoded by Bessemer rails. And Thomas Durant, vice-president and general manager, stressed speed, not workmanship. "You are doing too much masonry this year," Durant told a staff member; "substitute tressel (sic) and wooden culverts for masonry whenever you can for the present." Also, since trees were scarce on the plains, Durant and his chief engineer, Grenville Dodge, were hard pressed to make railroad ties, 2300 of which were needed to finish each mile of track. Sometimes they shipped in wood; other times they used the fragile cottonwood found in the Platte River Valley; often, though, they artfully solved their problem by passing it on to others. The UP simply paid top wages to tie-cutters and daily bonuses for ties received. Hordes of tie-cutters, therefore, invaded Nebraska, cut trees wherever they were found, and delivered freshly cut ties right up to the UP line. The UP leaders conveniently argued that, since most of Nebraska was unsurveyed, farmers in the way were therefore squatters and held no right to any trees on this "public land." Some farmers used rifles to defend their land; and, in the wake of violence, even Durant discovered "that it was not good policy to take all the timber."[3]

The rush for subsidies caused other building problems, too. Nebraska winters were long and hard; but, since Dodge was in a hurry, he laid track on the ice and snow anyway. Naturally the line had to be rebuilt in the spring. What was worse, unanticipated spring flooding along the Loup fork of the Platte River washed out rails, bridges, and telephone poles, doing at least $50,000 damage the first year. No wonder some observers estimated the actual building cost at almost three times what it should have been.[4]

By pushing rail lines through unsettled land, the transcontinentals invited Indian attacks, which caused the loss of hundreds of lives and further ran up the cost of building. The Cheyenne and Sioux harassed the road throughout Nebraska and Wyoming: they stole horses, damaged track, and scalped workmen along the way. The government paid the costs of sending extra troops along the line to help protect it. But when they left, the graders, tie-setters, track-layers, and bolters often had to work in teams with half of them standing guard and the other half working. In some cases, such as the Plum Creek massacre in Nebraska, the UP attorney admitted his line was negligent: it had sent workingmen into areas known to be frequented by hostile Indians.[5]

As the UP and CP entered Utah in 1869, the competition became fiercer and more costly. Both sides graded lines that paralleled each other and both claimed subsidies for this mileage. As they approached each other the workers on the UP, mostly Irish, assaulted those on the CP, mostly Chinese. In a series of attacks and counterattacks, with boulders and gunpowder, many lives were lost and much track was destroyed. Both sides involved Presidents Johnson and Grant in the feuding. With the threat of a federal investigation looming, the two lines finally compromised on Promontory Point, Utah, as their meeting place. There they joined tracks on May 10, with hoopla, speeches, and the veneer of unity. After the celebration, however, both of the shoddily constructed lines had to be rebuilt and sometimes relocated, a task that the UP didn't finish until five years later. As Dodge said one week before the historic meeting, "1 never saw so much needless waste in building railroads. Our own construction department has been inefficient."[6]

After the construction was completed, many were astonished at the costs of construction. The UP and CP, even with 44,000,000 acres of free land and over $61,000,000 in cash loans, were almost bankrupt. Two other circumstances helped to keep costs high. First, the costs of building a railroad, or anything else for that matter, were abnormally high after the Civil War. Capital and labor were scarce; also, even without the harsh winters and the Indians, it was costly to feed thousands of workmen who were sometimes hundreds of miles from a nearby town. Second, the officers of the Union and Central Pacific created their own supply companies and bought materials for their roads from these companies. The UP, for example, needed coal, so six of its officers created the Wyoming Coal and Mining Company. They mined coal for $2.00 per ton (later reduced to $1.10) and sold it to the UP for as high as $6.00 a ton. Even more significant, the Credit Mobilier, which was also run by UP officials, supplied iron and other materials to the UP at exorbitant prices. What they didn't make running the railroad, they made selling to the railroad.[7]

Many people then and now have pointed accusing fingers at the UP with its Credit Mobilier and its wasteful building. But this misdirects the problem. If we look at the subsidies instead, we can see that they dictated the building strategy and dramatically shaped the outcome. Granted, the leaders of the UP were greedy and showed poor judgment. But the presence of free land and cash tempted them to rush west, then made them dependent on federal aid to survive.

No wonder the UP courted politicians so carefully. In this arrangement they were more precious than freight or passengers. In 1866, Thomas Durant wined and dined 150 "prominent citizens" (including Senators, an ambassador, and government bureaucrats) along a completed section of the railroad. He hired an orchestra, a caterer, six cooks, a magician (to pull subsidies out of a hat?), and a photographer. For those with ecumenical palates, he served Chinese duck and Roman goose; the more adventurous were offered roast ox and antelope. All could have expensive wine and, for dessert, strawberries, peaches, and cherries. After dinner some of the men hunted buffalo from their coaches. Durant hoped that all would go back to Washington inclined to repay the UP for its hospitality. If not, the UP could appeal to a man's wallet as well as his stomach. In Congress and in state legislatures, free railroad passes were distributed like confetti. For a more personal touch, the UP let General William T. Sherman buy a section of its land near Omaha for $2.50 an acre when the going rate was $8.00. In case that failed, Oakes Ames, president of the UP, handed out Credit Mobilier stock to congressmen at a discount "where it would do the most good." It was for this act, not for selling the UP overpriced goods, that Congress censured Oakes Ames and then investigated the UP line.[8]

The airing of the Credit Mobilier scandal just four years after the celebrating at Promontory Point soured many voters on the UP. Others were annoyed because the UP was so inefficient that it couldn't pay back any of its borrowed money. Just as the UP was birthed and nurtured on federal aid, though, so it would have to mature on federal supervision and regulation.

In 1874, Congress passed the Thurman Law, which forced the UP to pay 25 percent of its net earnings each year into a sinking fund to retire its federal debt. Because the line was so badly put together, it competed poorly and needed the sinking fund money to stay afloat. Building branch lines to get rural traffic would have helped the UP, but the government often wouldn't give them permission. President Sidney Dillon called his line "an apple tree without a limb," and concluded, "unless we have branches there will be no fruit." Congress further squashed any trace of ingenuity or independence by passing a law creating a Bureau of Railroad Accounts to investigate the UP books regularly. Of these federal restrictions, Charles Francis Adams, Jr., a later president, complained: "We cannot lease; we cannot guarantee, and we cannot make new loans on business principles, for we cannot mortgage or pledge; we cannot build extensions, we cannot contract loans as other people contract them. All these things are [prohibited] to us; yet all these things are habitually done by our competitors." The power to subsidize, Adams discovered, was the power to destroy.

John M. Thurston, the UP's solicitor general, saw this connection between government aid and government control. The UP, he said, was "perhaps more at the mercy of adverse legislation than any other corporation in the United States, by reason of its Congressional charter and its indebtedness to the government, and the power of Congress over it.[9]

When Jay Gould took control of the UP in 1874, his solution was to use and create monopoly advantages to raise prices, fatten profits, and cancel debts. For examole, he paid the Pacific Mail Steamship Companv not to compete with the UP along the west coast. Then he raised rates 40 to 100 percent and, a few weeks later, hiked them another 20 to 33 percent. This allowed him to pay off some debts and even declare a rare stock dividend; but it soon brought more consumer wrath, and this translated into more government regulation and, eventually, helped lead to the Interstate Commerce Commission, which outlawed rate discrimination.[10]

It is sad to read of the UP struggling for survival in the 1870s and 1880s, only to collapse into bankruptcy in 1893. Yet it's hard to see how its history could have taken any other direction, given the presence of government aid. The aid bred inefficiency; the inefficiency created consumer wrath; the consumer wrath led to government regulation; and the regulation closed the UP's options and helped lead to bankruptcy.

Leland Stanford (1814-1893):

used his political and financial

power to prevent competing

railroads from entering California.

The Central Pacific did better, but only because its circumstances were different. Its leaders - Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, Charles Crocker, and Mark Hopkins - were united on narrow goals and worked together effectively to achieve them. These men, the "Big Four," focused mainly on one state, California, and used their wealth and political pull to dominate (and sometimes bribe) California legislators. Stanford, who was elected Governor and U.S. Senator, controlled politics for the Big Four and prevented any competing railroad from entering California. Profits from the resulting monopoly rates were added to windfall gains from their Contract and Finance Company, which was the counterpart of the Credit Mobilier. Unlike the UP leaders in the Credit Mobilier scandal, the Big Four escaped jail because the records of the Contract and Finance Company "accidentally" were destroyed. Without records, it was left to Frank Norris to tell the story of the CP monopoly in his novel, The Octopus. It was almost 1900 before privately funded railroads could muster the financial strength and the political muscle to take on the entrenched CP (later renamed the Southern Pacific) in California politics.[11]

In case Congress needed another lesson, the story of the Northern Pacific again featured government subsidies. Congressmen chartered the Northern Pacific in 1864 as a transcontinental running through the Northwest. They gave it no loans, but granted it forty sections of land per mile, which was twice what the UP received. Various owners floundered and even bankrupted the NP, until Henry Villard took control in 1881. Villard had come to America at age eighteen from Bavaria in 1853. Shortly after he arrived, he showed a flair for journalism; he won recognition for his writing during the Civil War. In his writing and in his speaking, Villard developed the ability to persuade others to follow him. He first became interested in the Northwest in 1874; he was hired as an agent for German bondholders in America and went to Oregon to analyze their investments. He liked what he saw and began to have grandiose visions about a transportation empire in the Northwest. He soon began buying NP stock and took charge of the stagnant railroad in 1881.[12]

Henry Villard (1835-1900): a political

entrepreneur who "rushed into the

wilderness to collect his subsidies."

Villard had many of the traits of his fellow transcontinental operators. First, like Jay Gould, he manipulated stock; in fact, he bought his NP shares on margin and used overcapitalized stock as collateral for his margin account. Second, like the Big Four on the CP, Villard liked monopolies. He even bought railroads and steamships along the Pacific coast, not for their value, but to remove them as competitors. Finally, like the leaders of the UP, Villard eagerly sought the 44,000,000 acres the government had promised him for building a railroad.

Villard's strategy, then, resembled that of the other builders. He had an added plus, though, in his skills in promoting and coaxing funds from wealthy investors. "I feel absolutely confident," he wrote, "that we shall be able to work results. that will astonish every participant." Hundreds of German investors, and others too, heeded the call for funds and sent Villard $8,000,000 to bring the NP to the west coast. Businessmen everywhere were amazed at Villard's persuasive ways. "This is the greatest feat of strategy I ever performed," Villard proclaimed, "and I am constantly being congratulated upon ... the achievement." So with his friends' $8,000,000, and with the government's free land, Villard pushed the NP westward and arrived in Seattle, Washington, in 1883. His celebration, however, was short-lived because that same year the NP almost declared bankruptcy and Villard was ousted.[13]

If we look at Villard's actions, we can see why he failed. First, like the other transcontinental builders, he rushed into the wilderness to collect his subsidies. Villard knew that the absence of settlement meant the absence of traffic, but his solution was to promote tourism as well as immigration. He thought tourists would pay to enjoy the beauty of the Northwest, so he built some of the line along a scenic route. This hiked Villard's costs because he had to increase the grade, the curvature, and the length of the railroad to accommodate the Rocky Mountain view. Villard also created some expensive health spas around the hot springs at Bozeman and in Broadwater County, Montana. He also put glass domes around the hot springs and built plush hotels near them to accommodate the throng of tourists he predicted would come. Despite lavish advertising in the east, though, the tourists went elsewhere and Villard went broke[14]

The federal aid and the foreign investors had given Villard some room for error. But he made other mistakes, too. He was so anxious to rush to the coast that he built when construction costs were high. They were much lower three years before and three years after he built. High costs meant high rates, and this deterred freight and immigrants from traveling along the NP. Villard could have cut some of these costs, but as Julius Grodinsky has observed of Villard, "Whatever was asked, he paid." He didn't bother to learn much about railroads; in fact, during 1883 he seems to have been more interested in leveling six houses in New York City to build a glamorous mansion, in which to entertain the city's elite. With the NP he thought he could promote immigration, tourism, scenic routes, health spas, and use the free land and foreign cash to cover the costs. When his bubble burst, the NP went bankrupt and the German investors were ruined. But not so Villard - from his mansion in New York City, he raised more money and took control of the NP again five years later. The smooth-talking Villard, however, still could not overcome his earlier errors. The poorly constructed Northern Pacific was so inefficient that even the Villard charm could not make it turn a profit. In 1893, the NP went bankrupt again and the Villard era was over.[15]

Villard's failure was pathetic but in some ways understandable. The American Northwest was a tough section for building a railroad. It had a sparse population and a rugged terrain. Oddly enough, though, one man did come along and did build a transcontinental through the Northwest. In fact, he built it north of the NP, almost touching the Canadian border. And he did it with no federal aid. That man was James J. Hill, and his story tells us a lot about the larger problem of federal aid to railroads.

Hill and the Great Northern

Hill's life could have made good copy for Horatio Alger. He was born in a log cabin in Ontario, Canada, in 1838. His father died when the boy was young, and he supported his mother by working in a grocery for $4.00 per month. He lost use of his right eye in an accident, so his opportunities seemed limited. But Hill was a risk-taker and a doer. At age seventeen he aimed for adventure in the Orient, but settled for a steamer to St. Paul. There he clerked for a shipping company and learned the transportation business. He was good at it and became intrigued with the future of the Northwest.[16]

The American Northwest was America's last frontier. The states from Minnesota to Washington made up one-sixth of the nation, but remained undeveloped for years. The climate was harsh and the terrain was imposing. There were obvious possibilities with the trees, coal, and copper in the region; but crossing it and connecting it with the rest of the nation was formidable. The Rocky Mountains divided the area into distinct parts: to the east were Montana, North Dakota, and Minnesota, which were dry, cold, flat, and, predictably, empty. It was part of what pioneers called "The Great American Desert." Once the Rockies were crossed, the land in Idaho and Washington turned green with forests and plentiful rain. But the road to the coast was broken by the almost uncrossable canyons and jagged peaks of the Cascade Mountains. Since the Northwest was fragmented in geography, remote in location, and harsh in climate, most settlers stopped in the lower Great Plains or went on to California.

To most, the Northwest was, in the words of General William T. Sherman, "as bad [a piece of land] as God ever made." To others, like Villard, the Northwest was a chance to grab some subsidies and create a railroad monopoly. But to Hill the Northwest was an opportunity to develop America's last frontier. Where some saw deserts and mountains, Hill had a vision of farms and cities. Villard might build a few swanky hotels and health spas, but Hill wanted to settle the land and develop the resources. Villard preferred to approach the Northwest from his mansion in New York City. Hill learned the Northwest firsthand, working on the docks in St. Paul, piloting a steamboat on the Red River, and travelling on snowshoes in North Dakota. Villard was attracted to the Northern Pacific because of its monopoly potential; Hill wanted to build a railroad to develop the region, and then to prosper with it.[17]

Hill's years of maturing in St. Paul followed a logical course; from investing in shipping, he switched to steamships, then to railroads. In 1878, he and a group of Canadian friends bought the bankrupt St. Paul and Pacific Railroad from a group of Dutch bondholders. We don't know whether or not he then had the vision to turn it into a privately financed transcontinental. The St. Paul and Pacific story, like that of the other transcontinentals, had been one of federal subsidies, stock manipulation, profit-taking on construction, and bankruptcy. Its ten miles of track were sometimes unconnected and were made of fifteen separate patterns of iron. Bridge material, ties, and equipment were scattered along the right-of-way. When Hill and his friends bought this railroad and announced their intention to complete it, critics dubbed it "Hill's Folly." Yet he did complete it, ran it profitably, and soon decided to expand it into North Dakota. It was not yet a transcontinental, but it was in the process of becoming one.[18]

As Hill built his railroad across the Northwest, he followed a consistent strategy. First, he always built slowly and developed the export of the area before he moved farther west. In the Great Plains this export was wheat, and Hill promoted dry-farming to increase wheat yields. He advocated diversifying crops and imported 7,000 cattle from England and elsewhere, handing them over free of charge to settlers near his line. Hill was a pump-primer. He knew that if farmers prospered, their freight would give him steady returns every year. The key was to get people to come to the Northwest. To attract immigrants, Hill offered to bring them out to the Northwest for a mere $10.00 each if they would farm near his railroad. "You are now our children," Hill would tell immigrants, "but we are in the same boat with you, and we have got to prosper with you or we have got to be poor with you." To make sure they prospered, he even set up his own experimental farms to test new seed, livestock, and equipment. He promoted crop rotation, mixed farming, and the use of fertilizers. Finally, he sponsored contests and awarded prizes to those who raised meaty livestock or grew abundant wheat.[19]

Unlike Villard, Hill built his railroad for durability and efficiency, not for scenery. "What we want," Hill said, "is the best possible line, shortest distance, lowest grades and least curvature that we can build. We do not care enough about Rocky Mountain scenery to spend a large sum of money developing it." That meant that Hill personally supervised the surveying and the construction. "I find that it pays to be where the money is being spent," noted Hill, but he didn't skimp on quality materials. He believed that building a functional and durable product saved money in the long run. example, he usually imported high quality Bessemer rails, even though they cost more than those made in America. He was thinking about the future, and quality building cut costs in the long run. When Hill constructed the solid granite Stone Arch Bridge - 2100 feet long, 28 feet wide, and 82 feet high - across the Mississippi River it became the Minneapolis landmark for decades.[20]

Hill's quest for short routes, low grades, and few curvatures was an obsession. In 1889, Hill conquered the Rocky Mountains by finding the legendary Marias Pass. Lewis and Clark had described a low pass through the Rockies back in 1805; but later no one seemed to know whether it really existed or, if it did, where it was. Hill wanted the best gradient so much that he hired a man to spend months searching western Montana for this legendary pass. He did in fact find it, and the ecstatic Hill shortened his route almost one hundred miles.[21]

As Hill pushed westward, slowly but surely, the Northern Pacific was there to challenge him. Villard had had first choice of routes, lavish financing from Germany, and 44,000,000 acres of free federal land. Yet it was Hill who was producing the superior product at a competitive cost. His investments in quality rails, low gradients, and short routes saved him costs in repairs and fuel every trip across the Northwest. Hill, for example, was able to outrun the Northern Pacific from coast to coast at least partly because his Great Northern line was 115 miles shorter than Villard's NP.

More than this, though, Hill bested Villard in the day-to-day matters of running a railroad. For example, Villard got his coal from Indiana, but Hill got his from lowa and saved $2.00 per ton. In the volatile leasing game, Hill outmaneuvered Villard and got a lower cost to the Chicago market. As Hill said, "A railroad is successful in the proportion that its affairs are vigilantly looked after."[22]

Villard may have realized he was outclassed, so he countered with obstructionism, not improved efficiency. One of Hill's partners alerted him to Villard's "egotistic stamp" and concluded that "Villard's vanity will be apt to lead him to reject any treaty of peace that does not seem to gratify his vain desire to obtain a triumph." Before Hill could move out of Minnesota, for example, the NP refused him permission to cross its line at Moorhead, along the Minnesota-North Dakota border. Local citizens apparently wanted Hill's line; and he wrote, "T had a letter from a leading Moorhead merchant today offering 500 good citizen tracklayers to help us at the crossing." Each move west that Hill made threatened Villard's monopoly. Ironically, Hill sometimes had to use the NP to deliver rails; when he did Villard sometimes raised rates so high that Hill used the Canadian Pacific when he could.[23]

Crony Politics & Lobbying

Villard found that manipulating politics was the best way to thwart Hill. For example, the gaining of right-of-way through Indian reservations was a thorny political issue. Legally, no railroad had the right to pass through Indian land. The NP, as a federally funded transcontinental, had a special dispensation. Hill, however, didn't, so the NP and UP tried to block Congress from granting Hill right-of-way through four Indian reservations in North Dakota and Montana. Hill gladly offered to pay the willing Indians fair market value for their land, but Congress stalled, and Hill said, "All our contracts (are] in abeyance until [this] question can be settled." Hill had to fight the NP and UP several times on this issue before getting Congress to grant him his right-of-way. "It really seems hard," Hill later wrote, "when we look back at what we have done in opening the country and carrying at the lowest rates, that we should be compelled to fight political adventurers who have never done anything but pose and draw a salary. "[24]

In the depression year of 1893, all the transcontinental owners but Hill were lobbying in Congress for more government loans. To one of them Hill wrote, "The government should not furnish capital to these companies, in addition to their enormous land subsidies, to enable them to conduct their business in competition with enterprises that have received no aid from the public treasury." He proudly concluded, "Our own line in the North...was built without any government aid, even the right of way, through hundreds of miles of public lands, being paid for in cash."[25]

Shortly after Hill wrote this, the Union Pacific, the Northern Pacific, and the Santa Fe all went bankrupt and had to be reorganized This didn't surprise Hill; he gloated, "You will recall how often it has been said that when the Nor Pac, Union Pac and other competitors failed, our company would not be able to stand.... Now we have them all in bankruptcy. while we have gone along and met their competition." In fact, the efficient Hill cut his costs 13 percent from 1894 to 1895.

Hill criticized the grab for subsidies, but here is the ironic twist: those who got federal aid ended up being hung by the strings that were attached to it. In other words, there is some cause and effect between Hill's having no subsidy and prospering and the other transcontinentals getting aid and going bankrupt. First, the subsidies, whether in loans or land, were always given on the basis of each mile completed. In this arrangement, as we have seen, the incentive was not to build a quality line, as Hill did, but to build quickly to get the aid. This resulted not only in poorly built lines but in poorly surveyed lines as well. Steep gradients meant increased fuel costs; poor building meant costly repairs and accidents along the line. Hill had no subsidy, so he built slowly and methodically. "During the past two years," Hill said in 1884, "we have spent a great deal of money for steel rails, balasting track, transfer yards, terminal facilities, new equipment, new shops, and in fact we have put the road in better condition than any railway similarly situated that I know of." Hill, then, had lower fixed costs than did his subsidized competitors.[26]

By building the Great Northern without government interference, Hill enjoyed other advantages as well. He could build his line as he saw fit. Until Carnegie's triumph in the 1890s, American rails were inferior to some foreign rails, so Hill bought English and German rails for the Great Northern. The subsidized transcontinentals were required in their charters to buy American-made steel, so they were stuck with the lesser product. Their charters also required them to carry government mail at a discount, and this cut into their earnings. Finally, without Congressional approval, the subsidized railroads could not build spur lines off the main line. Hill's Great Northern, in contrast, looked like an octopus, and he credited spur lines as critical to his success.

In debating the Pacific Railway Bill in the 1860s, some Congressmen argued that even if the federally funded transcontinentals proved to be inefficient, they should still be aided because they would increase the social rate of return to the United States. Some historians and economists, led by Robert Fogel, have picked up this argument, and it goes like this: the UP made little profit and was poorly built, but it increased the value of the land along the road and promoted farms and cities in areas that could not have supported them without cheap transportation. Fogel claims that the value of land along a forty-mile strip on each side of the UP was worth $4.3 million in 1860 and $158.5 million by 1880. Without the UP, this land would have remained unsettled and the U. S. would not have had the national benefits of productive farms, new industries, and growing cities in the West. To the nation, then, the high social rate of return justified the building of the UP, CP, NP, and Santa Fe railroads,[27]

What this argument overlooks is the negative social, economic, and political return to the United States that came with using federal subsidies to build railroads. The first thing to recognize is that the gain in social return that Fogel describes is temporary. If the government had not subsidized a transcontinental, then private investors like Hill would have built them sooner and would have built them better. Subsidy promoters tried to deny this argument at the time, but Hill's achievement shows that it would have been done, only at a slower (but more efficient) pace. We can dismiss the widely promoted view expressed in Congress by Rep. James H. Campbell: "This [Union Pacific] road never could be constructed on terms applicable to ordinary roads. ... It is to be constructed through almost impassable mountains, deep ravines, canyons, gorges, and over arid and sandy plains. The Government must come forward with a liberal hand, or the enterprise must be abandoned forever." The increase in social rate of return, then, would only be present until some private investor did what the government did first.[28]

Here is a key point: the gain in social return was only temporary, but the loss of shipping with an inefficient railroad was permanent. The UP and NP were, as we have seen, inefficient in gradients, curvature, length, quality of construction, repair costs, and use of fuel. This meant permanently high fixed costs for all passengers and freight using the subsidized transcontinentals.

The subsidizing of railroads cost the nation in other ways, too. First, the land that was given to the railroads could not be sold for revenue. Second, the giving of subsidies to one established a precedent and resulted in the giving of subsidies to many. When the government gave twenty million acres to the UP, the NP and others clamored for aid; the result was the giving of 131 million acres of land to various railroads. Third, the granting of all this land, and money too, made for shady business ethics and political corruption. The Credit Mobilier is an example of poor business ethics, and the CP's tight control over California politics is a sample of political corruption. Part of this corruption is reflected in the automatic monopolies that subsidized transcontinentals had. When Jay Gould doubled rates along parts of the UP, not much could be done. It took time to build privately financed lines; and, when they were done, they had to compete with a railroad that had, thanks to the government, millions of acres of free land and large cash reserves.

A final hidden cost of subsidizing railroads is seen in the mass of lawmaking, much of it harmful, all of it time-consuming, that state legislatures. Congress, and the Supreme Court did after watching the UP, CP, and NP in action. The publicizing of shoddy construction, the Credit Mobilier scandal, rate manipulating, and bankrupt health spas angered consumers; and angry consumers pestered their Congressmen to regulate the railroads. Much of the regulating, however, had unintended consequences and made the situation worse. For example, when the corruption in the building of the UP became known, there was public outrage followed by a congressional investigation. In the investigating, many were irritated that the UP had made no payment on its government loans. Congress, as we have seen, passed the Thurman Law, which forced the UP to pay 25 percent of its annual earnings toward retiring its $28 million debt to the government. The problem here is that the shoddy construction of the UP made for high fixed costs, and the lack of spur lines limited its chances for profits. This meant that the UP had to raise rates for passengers and freight to pay back its loans. The rate hikes, though, caused even more public outcry: many noticed, for example, that the UP and NP were charging more than the GN did; and this helped lead to demands for rate regulation. Congress obliged and, in 1887, created the Interstate Commerce Commission to investigate and abolish rate discrimination. This created two new problems: first, it was now illegal to give discounts. Hill argued that rate cutting had led to lower rates over the years and that this allowed the United States to capture a larger share of overseas trade. Hill insisted that the ICC law, if enforced (which it eventually was), would hurt railroads in domestic and overseas trade. Second, the ICC law eventually cost the taxpayers millions of dollars every year; it created a need for thousands of federally funded bureaucrats to listen to shippers all over the nation and to snoop into the detailed records of almost every railroad in the country.[29]

The issue of foreign trade is important and was hotly disputed during Congress' debates on the transcontinentals. Advocates of federal aid strongly argued that subsidized railroads would capture foreign trade and increase national wealth. "Commerce is power and empire," said Senator William M. Gwin of California. "Give us, as this [Union Pacific) Railroad would, the permanent control of the commerce and exchanges of the world, and in the progress of time and the advance of civilization, we would command the institutions of the world." Yet the UP and NP were so inefficient, they couldn't even capture or develop the trade of their own regions, least of all the world. If Hill hadn't come along and built the privately financed Great Northern, the United States might have forever lost opportunities to capture Oriental markets.[30]

Once he completed the GN, he studied the opportunities for trade in the Orient and marveled at its potential. "If the people of a single province of China should consume [instead of rice] an ounce a day of our flour," Hill wistfully said, "they would need 50,000,000 bushels of wheat per annum, or twice the Western surplus." The key, Hill believed, was "low freight rates"; and these he intended to supply. In 1900, he plowed six million dollars into his Great Northern Steamship Company and shuttled two steamships back and forth from Seattle to Yokohama and Hong Kong. Selling wheat was only one of Hill's ideas. He tried cotton, too. Ever the pump-primer, Hill told a group of Japanese industrialists he would send them cheap Southern cotton, and deliver it free, if they would use it along with the short-staple variety they got from India. If they didn't like it, they could have a refund and keep the cotton. This technique worked, and Hill filled many boxcars and steamships with Southern cotton destined for Japan. Hill's railroads and steamships also carried New England textiles to China. In 1896, American exports to Japan were only $7.7 million; but nine years later, with Hill in command, this figure jumped to $51.7 million.[31]

An even greater coup may have been Hill's capturing of the Japanese rail market. Around 1900, Japan began a railroad boom and England and Belgium made bids to supply the rails. In this case, the Japanese may have underestimated Hill: it didn't seem likely that he could be competitive if he had to buy rails in Pittsburgh, ship them to the Great Northern, carry them by rail to Seattle, then by steamship to Yokohama. Hill was so efficient, though, and so eager for trade in Asia, that he underbid the English and the Belgians by $1.50 per ton and captured the order for 15,000 tons of rails. Hill was spearheading American dominance in the Orient.[32]

Hill worked diligently to market the exports of the Northwest. Wheat from the plains, copper from Montana, and apples from Washington all got Hill's special attention. Without Hill's low freight rates and aggressive marketing, some of these Northwest products might never have been competitive to export. Washington and Oregon, for example, were covered with Western pine and Douglas fir trees. But it was Southern pine that had dominated much of the American lumber market. Hill could provide the lowest freight rates, but he needed someone to risk harvesting the Western lumber. He found Frederick Weyerhauser, his next-door neighbor, and sold him 900,000 acres of Western timberland at $6.00 an acre. Then Hill cut freight costs from ninety to forty cents per hundred pounds, and the two of them captured some of the Midwestern lumber market and prospered together.[33]

Free Trade vs. Government Regulation

Hill became America's greatest railroad builder, he believed, because he followed a consistent philosophy of business. First, build the most efficient line possible. Second, use this efficient line to promote the exports in your section - in other words you must help others before you can be helped. Third, do not overextend; expand only as profits allow. Hill would probably have agreed with Thomas Edison that genius is one percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration. Few people were willing to exert the perspiration necessary to learn the railroad business and apply these principles. Many, like Villard, Gould, and Stanford, took the easy route and chased subsidies, hiked rates, and manipulated stock; but this approach never built a winning railroad. "If the Northern Pacific could be handled as we handle our property," Hill said, "it could be made a great property ... but it has not been run as a railway for years, but as a device for creating bonds to be sold." Hill understood markets, prices, and human nature; when he saw what his rivals were doing, he ceased to fear them.

The only thing that Hill did seem to fear was the potential for damage when the federal government stepped in to direct the economy. He understood why this happened - why people pressured Congress to involve itself in economic matters. California, isolated on the Pacific coast, wanted the cheap goods that a railroad would bring. So Senator Gwin lobbied in Congress for the UP. American steel producers wanted to sell more steel, so they pushed Congress to put a tariff on imported steel. Hill's problem was that, when his rivals were subsidized and when tariffs forced him to pay 50 percent more for English steel, he had to be twice as good to survive. One way out, which Hill took, was to support those politicians in the Northwest who would fight subsidies and high tariffs, and who would urge Congress to give him the right-of-way through Indian land.[34]

What Hill ultimately deplored more than tariffs and subsidies were the ICC and the Sherman Anti-trust Act. Congress passed these vague laws to protest rate hikes and monopolies. They were passed to satisfy public clamor (which was often directed at wrong-doing committed by Hill's subsidized rivals). Because they were vaguely written, they were harmless until Congress and the Supreme Court began to give them specific meaning. And here came the irony: laws that were passed to thwart monopolists, were applied to thwart Hill.

The ICC, for example, was created in 1887 to ban rate discrimination. The Hepburn Act, passed in 1906, made it illegal for railroads to charge different rates to different customers. This law was partly aimed at rate manipulators like Jay Gould. But it ended up striking Hill, who now could not offer rate discounts on exports traveling on the Great Northern en route to the Orient. Hill had given the Japanese and Chinese special rates on American cotton, wheat, and rails to wean them to American exports. But the Hepburn Act, according to Hill, immediately cut in half American trade to these countries. Hill testified vigorously during the Senate hearings that preceded the Hepburn Act, but was ignored. He was furious that he now had to publish his rates and give all shippers anywhere the special discount he was giving the Asians to capture their business. Since he couldn't do this and survive, he eventually sold his ships and almost completely abandoned the Asian trade [35]

"Rates vary with conditions," Hill said.

They vary from day to day, almost. I was much struck by some of the questions [addressed to the previous witness during the Hepburn Act hearings] as the difficulty in fixing what is a reasonable rate by law. You are dealing with the questions that exist today. Can you apply the conditions that exist today to tomorrow or next week or next month? It is absolutely impossible...The Hepburn Act, though, said rates had to be made public, applied equally to all shippers, and could not be changed without thirty days notice. American exports to Japan and China dropped 40 percent ($41 million) between 1905 and 1907, and we will never know how much trade, domestic and foreign, was lost elsewhere.[36]

Another federal law that was aimed at others, but which struck Hill instead, was the Sherman Anti-trust Act. As written, the Sherman Act banned "every combination ... in restraint of trade." This vaguely written law was an immediate problem because every act of trade potentially restrains other trade. This meant that the courts would have to decide what the law meant. The first test of the Sherman Act the E. C. Knight case (1895), liberated entrepreneurs to freely buy and sell. The American Sugar Refining Company had bought the E. C. Knight company and thereby held 98 percent of the American sugar market. The Supreme Court upheld this acquisition because no one had tried to "put a restraint upon trade or commerce." No one had stopped anyone else from producing sugar and competing with American Sugar Refining. Therefore, the trade was legal even though "the result of the transaction ... was creation of a monopoly in the manufacture of a necessary of life ..." In fact, other sugar producers did enter the market and steadily whittled the market share of American Sugar Refining from 98 to 25 percent by 1927.[37]

With the E. C. Knight case the law of the land, Hill saw no problem when he created the Northern Securities Company in 1901. After the Panic of 1893, Hill bought a controlling interest in the bankrupt NP and sometimes used it to ship his own freight. In 1901, Hill added the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy to his holdings; this allowed him to tap markets to the south in lumber, meat-packing, and cotton. That same year he placed his stock in the GN, NP, and CB&Q in a holding company called the Northern Securities Company. Hill pointed out that in doing this he was not restraining trade; he was combining three smaller companies he already controlled into one larger company. Actually, competition among the transcontinentals was keener than ever. Edward H. Harriman had taken over the bankrupt UP after the Panic of 1893 and, free of governmental restrictions, had plowed $25 million into new track, new routes, new equipment, and spur lines. He adopted Hill's philosophy of building an efficient railroad and promoting the exports of the region. Harriman even bought steamships and prepared to challenge Hill in the Orient. When Harriman tried to buy into the NP, a stock fight resulted, and financier ]. P. Morgan suggested the creating of a holding company, the Northern Securities, to prevent stock manipulation on Wall Street. Hill would be president of the Northern Securities and therefore keep control of his three railroads; Harriman would serve on the board of directors. Competition was not stifled; in fact, rates fell on both the GN and the UP in the two years after the Northern Securities was created.[38]

Hill was therefore disappointed when President Theodore Roosevelt urged the Supreme Court to strike down the Northern Securities under the Sherman Act. He called the Northern Securities a "very arrogant corporation" and Hill a "trust magnate, who attempts to do what the law forbids." But, of course, no one knew what the Sherman Act did or did not forbid. To lead his defense, Hill hired John G. Johnson, who was the "successful warrior" in the E. C. Knight case. Johnson defended the Northern Securities in much the same way he had defended the E. C. Knight Company. He argued that the Northern Securities did not restrain trade or bar other railroads from entering the Northwest; he then attacked the Sherman Act for being "so obscurely written that one cannot tell when he is violating (it]..." With the E. C. Knight case as a precedent, with rates falling on Hill's railroads, and with competition stiff between the GN and the UP, Johnson argued his case with confidence.[39]

In 1904, however, in a landmark case, the Supreme Court decided five to four against the Northern Securities. It had to be dissolved. Hill was especially irritated at Justice John M. Harlan, who wrote the majority opinion. The Northern Securities was, according to Harlan, "within the meaning of the [Sherman] Act, a 'trust'; but if it is not it is a combination in restraint of interstate and international commerce; and that is enough to bring it under the condemnation of the act." Harlan continued with a devastating statement: "The mere existence of such a combination. ..constitute[s] a menace to, and a restraint upon, that freedom of commerce which Congress intended to recognize and protect, and which the public is entitled to have protected.''[40]

The Northern Securities decision, then, overturned the E. C. Knight case. Now "the mere existence" of a large corporation was seen as a threat to trade and therefore unlawful. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote a dissent which credited this astonishing verdict to an unsophisticated, but widespread belief among the public, in Congress, and in the courts that big corporations must necessarily be bad ones. "Great cases," Holmes concluded, "make bad law." Meanwhile Hill had to abolish the Northern Securities, as well as his trade with the Orient.[41]

Conclusion

James J. Hill: He built the best railroad in America

and used it to beat subsidized rivals time and again.

A look at the story of Hill and the railroads shows again the harmful, but unintended consequences that followed federal tinkering with the economy. The goals for federal intervention sounded so noble: subsidize a railroad to conquer the West and then the world; strike down those corporations that "restrain trade." Yet these noble goals were soon lost in an eddy of tragic consequences. In the case of the Sherman Act, Harlan's interpretation was applied again and again. Since "the mere existence of such a combination" as the Northern Securities was bad, all large corporations now had to fear prosecution. Just how much this hurt American trade, at home and abroad will never be known. Robert Sobel and other business historians have argued that this fear of being too big made some corporations stifle innovation and reduce their dominance in their industries in order to protect inefficient competitors. General Motors and IBM are frequently cited as examples of companies that dulled their competitive edge to help their rivals survive.[42]

Hill was sad and predicted that the ICC and the Sherman Act would ruin American railroads and threaten cheap trade throughout the nation. A 72-year-old Hill would even write a book, Highways of Progress, to argue this point. But his last days seem to have been happy. He had built the best railroad in America and had used it to beat subsidized rivals time and again. He helped open the Northwest to settlement and the Orient to American trade. He had made a difference in the way the world worked. To some viewers, he was the real hero in the drama of the American transcontinental railroads.

Notes

-

John A. Garaty, The American Nation: A History of the United States, 7th ed. (New York: Harper Collins, 1991), 497.

Yames F. Stover, American Railroads (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961), 67; Henry Kirke White, History of the Union Pacific Railtony (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1895).

Robert G. Athearn, Union Pacific Country (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1971), 37-38, 43-44.

J. R. Perkins, Trails, Rails, and War: The Life of General G. M. Dodge (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1929), 207. See also Stanley P. Hirshson, Grenville M. Dodge: Soldier, Politician, Railroad Pioneer (Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 1967)

Athearn, Union Pacific Country, 200-03.

Perkins, Dodge, 231-33, 238. See also William F. Rae, Westward By Rail:

The New Route to the East (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1871).

Athearn, Union Pacific Country, 139-42.

Perkins, Dodge, 205-06; Athearn, Union Pacific Country, 153.

Athearn, Union Pacific Country, 224, 337-40, 346.

Julius Grodinsky, Transcontinental Railway Strategy, 1869-1893: A Study of Businessmen (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1962), 70-71.

For a full description of the Central Pacific, see Oscar Lewis, The Big Four: The Story of Huntington, Stanford, Hopkins, and Crocker, and of the Building of the Central Pacific (New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1938).

Grodinsky, Transcontinental Railway Strategy, 137. For A fuller account of Villard's career, see James B. Hedges, Henry Villard and the Railways of the Northwest (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1930).

Hedges, Villard, 112-211; Grodinsky, Transcontinental Raiway Strategy, 140, 185

Mildred H. Comfort, James Jerome Hill, Railroad Pioneer (Minneapolis: T. S. Denison, 1973), 64-65.

Grodinsky, Transcontinental Railway Strategy, 137.

Albro Martin, James J. Hill and the Opening of the Northwest (New York:

Oxford University Press, 1976), 16-45; Stewart Holbrook, James J. Hill: A Great Life in Brief (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1955), 9-23.

Stover, American Railroads, 76; Holbrook, Hill, 13-42.

Martin, Hill, 122-40, 161-71, passim; Holbrook, Hill, 44, 54-68.

Martin, Hill, 183; Robert Sobel, The Entrepreneurs: Explorations Within the American Business Tradition (New York: Weybright and Talley, 1974), 140; Howard L. Dickman, "James Jerome Hill and the Agricultural Development of the Northwest" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 1977), 67-144.

Holbrook, Hill, 93; Martin, Hill, 366.

Martin, Hill, 381-83; Comfort, Hill, 67-70.

Martin, Hill, 233, 236.

Ibid., 225, 239-43, 264-70.

Ibid., 298, 307, 338, 346, 494.

Ibid., 410-11.

Ibid., 300, 414-15, 442.

Robert W. Fogel, The Union Pacific Railroad (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1960), 99-100.

Ibid., 25. Carl Degler has a variant of this viewpoint. He says, "In the West, where settlement was sparse, railroad building required government assistance." Later, he adds, "By the time the last of the four pioneer tran-scontinentals, James J. Hill's Great Northern, was constructed in the 1890s, private capital was able and ready to do the job unassisted by government." This argument suggests that the key variable is the timing of the building, not the subsidy itself. The main problem here is that Hill's transcontinental across the sparse Northwest, especially with the Canadian Pacific above him and the Northern Pacific below him, was just as risky as the Union Pacific was. That's why it was called "Hill's Folly." Also, Hill was building at roughly the same time as the Northern Pacific; but Hill succeeded, while the Northern Pacific failed. Finally, we need to remember that, in 1893, Hill flourished, while the Union Pacific, the Northern Pacific, and the Santa Fe all went into receivership. This brings us back to the subsidy as the problem, not the timing of the gift. See Carl Degler, The Age of the Economic Revolution, 1876-1900 (Glenview, III.: Scott, Foresman and Co., 1977), 19-20.

For a development of much of this argument, see Albro Martin, Enterprise Denied: Origins of the Decline of American Railroads, 1897-1917 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1971). See also Martin, Hill, 535-44.

Fogel, Union Pacific Railroad, 41.

Holbrook, Hill, 161-63; Sobel, Entrepreneurs, 138; James J. Hill, Highways of Progress (New York: Doubleday, Page, and Co., 1910), 156-69.

Holbrook, Hill, 162-63.

Ibid., 161; Sobel, Entrepreneurs, 135; Martin, Hill, 464-65.

Martin, Hill, 298-99, 307, 347, 442, 462.

Hill, Highways of Progress, 156-184; Holbrook, Hill, 163; Ari and Olive Hoogenboom, A History of the ICC: From Panacea to Palliative (New York: W. W. Norton, 1976), 49-59.

Hill, Highways of Progress, 169; Martin, Hill, 540.

Dominick T. Armentano, The Myths of Antitrust: Economic Theory and Legal Cases (New Rochelle, N.Y.: Arlington Press, 1972), 56-58.

Martin, Hill, 494-523.

Armentano, The Myths of Antitrust, 58-62; Martin, Hill, 515, 518.

Armentano, The Myths of Antitrust, 58-59.

Martin, Hill, 519.

Robert Sobel, The Age of Giant Corporations: A Microeconomic History of American Business, 1914-1970 (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press,' 1972),

189-94.